Industrialization is the engine behind our prosperity, yet it also has a dark side. The newly created working class often had to work under horrible conditions in dangerous factories and mines for incredibly low wages. Even children were forced to work long hours in these dangerous places. When awareness about these horrible conditions grew, it became increasingly clear that it was necessary to protect the rights of workers. Various philosophers and activists began to advocate for trade unions and social programs to ensure a decent standard of living for everyone.

Some thinkers, however, went much further and advocated for the complete overthrow of the capitalist system. The most influential of these thinkers was Karl Marx, who envisioned a system free from competition and private property, where the means of production were collectively owned and the produce was shared equally among the people. He called his system communism.

In the 20th century, his system was implemented all over the world, but with disastrous consequences. Without market incentives and competition, all communist economies collapsed, leading to massive shortages and famine wherever it was tried. The system also turned out to require brutal governmental oppression to quell dissident voices. Some estimates place the death toll of communism at 100 million.

The working class

In many ways, the 19th century was a time of optimism for the West. This was especially true for Britain, which became the world’s largest manufacturer and the wealthiest country on earth. The economist Keynes vividly described the sentiment of the time:

Escape was possible [into the middle and upper classes] for any man of capacity or character at all exceeding the average, for whom life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages.

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. He could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share—without exertion or even trouble—in their prospective fruits and advantages. […] He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality. [386]

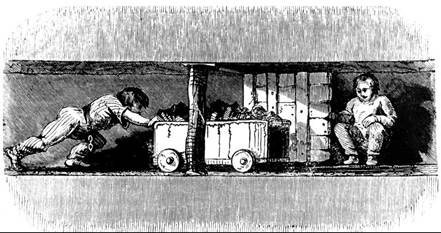

However, at the start of the Industrial Revolution, not everyone profited from this new entrepreneurial spirit. In particular, craftsmen and artisans were suddenly unable to compete with the cheap, mass-produced factory goods and new farming technologies required fewer people to work the fields. Those who lost their jobs fell out of the middle class and often came to work in factories, forming a new class known as the working class. The sheer number of available workers for factory work, combined with low job requirements, kept their wages low and made the workers easily replaceable, which made them vulnerable to exploitation. Workdays were usually 12 to 16 hours long for six days a week (or seven when behind on quota). Factory work was highly repetitive and often noisy and dangerous. People worked with poisonous chemicals and the early steam engines would sometimes explode due to high pressure. Work conditions in the coal mines were perhaps the worst, requiring heavy labor in often claustrophobic underground passageways while breathing in coal dust. Mines also often collapsed or flooded. To make matters even worse, children, sometimes as young as five years old, also had to work under these circumstances. Boys were chained around the waist to haul carts of coal through mineshafts, while girls worked underground in complete darkness for 12 hours straight to open and close underground passage doors (see Fig. 585 and Fig. 586). This improved somewhat in 1833 when child labor in Britain was prohibited before the age of nine.

The living conditions of the working class were horrifying as well. They often lived in small row houses without indoor plumbing, toilets, or windows, and sometimes with entire families living in a single room. Built close to the factories, the air was often filled with smoke and toxic elements. Combined with poor diets and the outbreak of disease, the life expectancy of factory workers in Manchester dropped to only 17 years.

Fig. 585 – A child opening an underground door in a coal mine, while another child pushes a cart of coal through (19th century)

Fig. 586 – A mother carrying a cart of coal, while her children push the cart from behind.

Workers at the time also had no political representation and little other opportunities to get their voices heard, but various influential journalists, philosophers, and politicians jumped in to speak out on their behalf. In 1819, the Manchester Observer called for a public demonstration to demand reform, to which 60,000 people showed up. When troops were deployed, they clashed with the protesters in what came to be known as the Peterloo Massacre, resulting in 11 deaths. Two years later, the Manchester Observer was forced to close, but in the same year, The Guardian was founded to take its place.

In 1832, the British Parliament also inquired into the matter by interviewing factory workers. The interviews are documented in the Sadler Report. One worker told them the following:

“Have you ever been employed in a factory?” “Yes.” “At what age did you first go to work in one?” “Eight.” [...] “Will you state the hours of labor at the period when you first went to the factory, in ordinary times?” “From 6 in the morning to 8 at night.” “Fourteen hours?” “Yes.” [...] “When trade was brisk what were your hours?” “From 5 in the morning to 9 in the evening.” “Sixteen hours?” “Yes.” [...] “During those long hours of labor could you be punctual; how did you awake?” “I seldom did awake spontaneously; I was most generally awakened or lifted out of bed, sometimes asleep, by my parents.” “Were you always in time?” “No.” “What was the consequence if you had been too late?” “I was most commonly beaten.” “Severely?” “Very severely, I thought.”

Fig. 587 – Child Labor in a coal mine in the United States, by Lewis Hine (c. 1912) (National Archives, PD)

A female worker spoke about her experiences as a young girl:

“What time did you begin to work at a factory?” “When I was six years old.” [...] “What were your hours of labor in that mill?” “From 5 in the morning till 9 at night.” [...] “Suppose you flagged a little, or were too late, what would they do?” “Strap us.” [...] “Girls as well as boys?” “Yes.” “Have you ever been strapped?” “Yes.” “Severely?” “Yes.” “Could you eat your food well in that factory?” “No, indeed I had not much to eat, and the little I had I could not eat it, my appetite was so poor, and being covered with dust; and it was no use to take it home, I could not eat it, and the overlooker took it, and gave it to the pigs.” [387]

Various writers also gave voice to the working class. The German communist and businessman Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) investigated the working conditions of the working class in Manchester, which he vividly described in his book The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844). The British writer Charles Dickens (1812–1870) used his literary talents to portray the abuses suffered by the working class in his work Hard Times (1854).

As the working class grew in size, they did manage to organize themselves by forming trade unions to fight for better wages, safer working conditions, reduced work hours, and accident insurance. In this way, the workers came to have a voice, despite still having no voting rights.

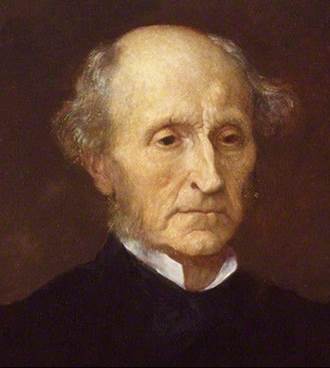

John Stuart Mill

A great example of this shift can be found in the work of John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Mill had been a child prodigy who started learning Greek at three, Latin at eight, and most of the classical canon and algebra by twelve. Earlier in his career, when only eighteen years old, he wrote On Religious Persecution, in which he defended the jailed journalist and publisher Richard Carlile (1790–1843), who had covered the Peterloo Massacre and also made blasphemous books available to the lower classes, including Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason. In his essay, Mill made the case that banning books was indefensible and counterproductive. Even if the case could be made that Deist works were too dangerous for the uneducated lower classes, the solution should be to educate them instead of banning these works. He also encouraged the working class to think for themselves and to “seek a share in the government.”

In Mill’s most famous work, On Liberty (1859), he advocated for a free-market economy and limited government interference. He claimed the government should only interfere in individual liberties to prevent people from harming each other, which he called the harm principle. His definition of harm included bodily harm and theft of property, but not “mere offenses,” such as offensive speech. In fact, he considered free speech essential, as society needs the greatest possible diversity of opinion to progress. In case speech contains truth, he reasoned, it can improve society, and in case it contains falsehood, it can be countered by better arguments. He even claimed falsehoods can help refine the correct opinion, as arguments become stronger in “collision with error,” and heated argument can keep ideas from declining into mere dogma. Sure, these collisions can be unpleasant, but that is the price of progress. Free speech is also important to resist society’s pressure to “impose […] its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them” [136] or what he called the “tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling.” [388] Although most of these points weren’t completely new, he articulated them like no other:

If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind. [388]

And also:

We can never be sure that the opinion we are endeavoring to stifle is a false opinion; and if we were sure, stifling it would be an evil still. [136]

While Mill would continue to promote economic competition, he wrote in other works that he did saw the need for some interventionist policies. A relatively free market was necessary as it solved the problem of production, but some government actions seemed necessary, such as regulating hours of labor, checking the quality of goods, and most importantly government-funded public education. This, he claimed, was necessary for democracy to function, for “so long as education continues to be so wretchedly imperfect, we[23] dread the ignorance and especially the selfishness and brutality of the masses.” [388] People should be able to read the news in order to make an informed decision in the voting booth. This was especially important since Mill was an early proponent of universal suffrage, wanting to extend the vote to the poor and also to women (a position he defended in his work called The Subjection of Women).

Mill even fantasized about a reformed form of capitalism, which included some voluntary collectivist approaches to property ownership to help emancipate the working class. Perhaps, he argued, workers could collectively own or hire the factories they worked in or they could form small-scale cooperative communities. He did not refrain from calling himself a socialist on these matters, yet he was strongly opposed to full-scale communism throughout his career, as this removes incentives to increase production and requires tyranny over the individual (more on this later in the chapter).

Fig. 588 – John Stuart Mill (1873) (National Portrait Gallery, Britain)

As the 19th century progressed, persistent activism for the working class caused the situation to improve. But the most important factor was the extreme rise in economic prosperity itself, which lifted the poor out of poverty on an unprecedented scale, finally delivering on the promise of capitalism after a few decades of hell.

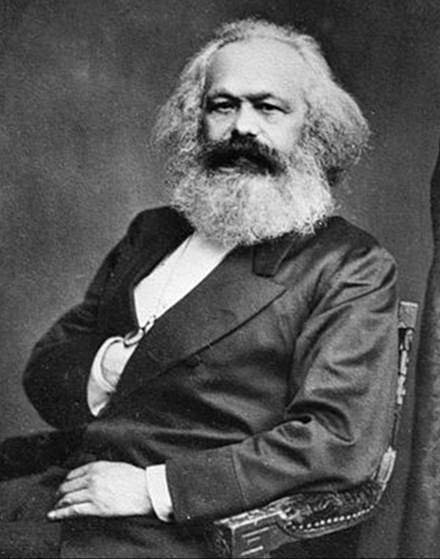

Karl Marx

One of the most important critics of the exploitation of the working class was Karl Marx (1818–1883). Marx was worried about the effects of industrialization on the human condition, claiming the repetitive work caused factory workers to feel dehumanized and alienated from their produce. Marx wrote that the capitalist system concentrated most of the wealth in the hands of a small elite of factory owners who owned the means of production (known as the bourgeoisie), at the expense of the poorer class (the proletariat). He reasoned that as factories would continue to require fewer workers, they would continue to drive wages down. In time, he predicted, these wages would drop below subsistence level. At that point the working class would have no choice but to start a violent revolution to overthrow capitalism. Speaking in almost apocalyptic terms, he urged the working class to get ready for their final fight to overthrow the system. He ended his Communist Manifesto (1848) with the famous lines:

Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite! [389]

Yet at the time Marx wrote Das Kapital, in 1867, the wages of the poor in Britain were already steadily going up, not down, undercutting his argument.

Fig. 589 – Karl Marx by John Mayall (International Institute of Social History)

Marx’s prediction of revolution fit perfectly into his overarching theory to explain the evolution of human history. Marx believed that economic forces, especially the conflict between economic classes, were the most powerful shapers of history, more so than individual actions. This view of the world is powerfully described in the opening paragraph of his Communist Manifesto, which he co-authored with Friedrich Engels:

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes. [389]

According to Marx, class struggle had already replaced feudalism with capitalism and would eventually replace capitalism with communism. Marx believed this transformation would come to pass by necessity, through scientific deduction. He predicted that the working class would abolish class distinctions and private property, thereby ending inequality. Instead, all means of production would be publicly owned, and the goods and services produced would be shared among the population. Instead of competition, all people would learn to cooperate selflessly, each doing their part. This, he believed, would eventually allow even the state itself to disappear. Marx also predicted that the communist system would produce such an abundance of goods and services that everyone would be able to freely acquire what they needed. The motto for this utopia, which was popularized by Marx but can be found in earlier works, became:

From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs. [390]

Serious about moving society towards this goal, Marx claimed to be both a political activist and a philosopher. About this, he wrote:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it. [391]

Lenin

Marx had predicted that the communist revolution would occur in one of the most developed capitalist countries, but instead, it first broke out in Russia, which was still largely agrarian. Lacking industrial capabilities, Russia suffered badly during the First World War, weakening the position of Russia’s ruler Tsar Nicholas II Romanov (1868–1918). Taking advantage of the instability, revolutionaries instigated the February Revolution of 1917, which resulted in the arrest of the tsar and the installation of a provisional government with a mandate to organize democratic elections. But later that same year, the communist Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) overthrew the government and established the first communist state.

Lenin, born as Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, was born into the lower nobility but became interested in the plight of the working class. He rejected both religion and liberal democracy and instead passionately turned toward communism. Lenin worked his way up the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, and in 1903, he forced a split in the party, leading his militant Bolshevik (“Majority”) faction away from the more moderate and democratic Menshevik (“Minority”) faction. In 1917, after being exiled twice from Russia for sedition, Lenin was sent back by the Germans, who hoped he would destabilize Russia. On arrival in Petrograd, Lenin announced his “April Theses,” calling for the Bolsheviks to stop cooperating with the government, liberals, and democratic socialists. Instead, they were to give their full support to workers’ councils, called soviets. Using catchy slogans, such as “All Power to the Soviets!” and “Bread, Peace, and Land,” he managed to get the working class riled up to support his cause.

In July of 1917, Lenin tried to stage a coup, which failed, but later that year, in what came to be known as the October Revolution, or Red October, he succeeded. The revolutionary Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) coordinated the operation while Lenin was in hiding. Once in charge of the city, they announced having taken power in the name of the soviets and renamed themselves the Communist Party. Lenin positioned himself as a dictator, giving a new interpretation to the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” which Marx had predicted as an intermediate stage between a capitalist and a communist economy. He wrote:

Dictatorship means nothing more nor less than authority untrammeled by any laws, absolutely unrestricted by any rules whatever, and based directly on force. [392]

Shortly after gaining power, the Bolsheviks made other political parties illegal, shut down newspapers, dismissed the new democratically elected assembly, replaced the courts with revolutionary tribunals, and executed the tsar and his family, shooting them in a cellar in 1918. The Bolsheviks also created a secret police, known as the Cheka, which was authorized to carry out the Red Terror against counterrevolutionaries, killing thousands of people. A concentration camp system, known as the GULAG, held an estimated 100,000 prisoners in the 1920s.

Lenin explicitly saw his revolution as the start of an international movement. He reasoned that the revolution had started in Russia because it was the weakest link in the capitalist world system, but eventually the revolution would create a worldwide cascade of revolutions, including in the developed countries. To facilitate this, Lenin started the Communist International, an organization devoted to exporting the revolution to other countries by setting up and supporting communist parties. Trotsky referred to it as the “General Staff of the World Revolution.” This movement would become very successful. At the peak of the Cold War, a stunning third of the world’s population would live under communist regimes.

Still in 1917, a complicated civil war broke out between the Bolshevik Red Army and the anti-Bolshevik White Army. The civil war turned out to be more devastating for Russia than the First World War, leading to an estimated 7 to 10 million deaths. Being better organized, the Bolsheviks increased their territory over the years and finally won in 1922 when they founded the Soviet Union, officially known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

The wars in Russia had caused massive destruction, a crashed economy, and famine. On top of this, Russia had very few factories and its labor force consisted mainly of illiterate peasants, yet Lenin remained confident in transforming his country into the first communist society. This first required him to start the process of industrialization:

There can be no question of rehabilitating the national economy or of communism unless Russia is put on a different and a higher technical basis than that which has existed up to now. Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country, since industry cannot be developed without electrification. This is a long-term task which will take at least ten years to accomplish, provided a great number of technical experts are drawn into the work. [393]

Fig. 590 – Vladimir Lenin by Soyuzfoto (c. 1920) (Library of Congress, United States)

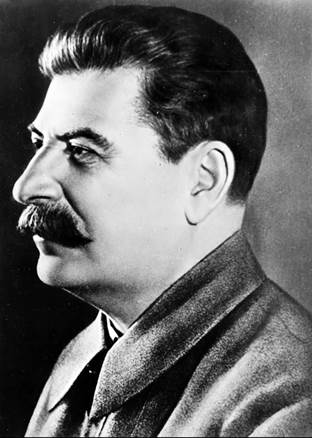

Fig. 591 – Joseph Stalin (c. 1942) (Library of Congress, United States)

In line with Marxism, the communists took direct control over the economy. They shut down the market and took control of international trade, banks, factories, and farmland. In 1921, the GOSPLAN, or State Planning Commission, was established to further work out the goals for this planned economy.

But then, in 1922, Lenin was largely incapacitated by a stroke. He died two years later.

Stalin

Leon Trotsky seemed the obvious candidate to take Lenin’s place as he was charismatic, intelligent, and had gained a lot of respect for his role in the revolution. Yet, he was unexpectedly outsmarted by an unlikely leader named Ioseb Dzhugasvili, commonly known as Joseph Stalin (1878–1953). Stalin, whose name means “Man of Steel,” had joined the Bolsheviks in 1903 as a bank robber for the party, but eventually managed to work himself up to become general secretary of the Communist Party. Stalin was short and had a face scarred by smallpox, a squeaky voice with a strong Georgian accent, and a partially crippled arm. He also hadn’t played an important role in either the party or the revolution. Although this put him at a disadvantage, it also caused his competitors to underestimate both his ambition and his superb bureaucratic skills. He cleverly positioned many of his supporters in key party positions in the Soviet system, and as a result, they became very loyal to him. He also opportunistically shifted his position within the Bolshevik party for political gain. When joining the Right Opposition, Stalin engineered Trotsky’s expulsion from the party in 1927 and had him exiled. Stalin then joined the Left Opposition and expelled his formidable rivals from the right. As a result, he was in complete control of the Soviet Union by 1928.

Once in charge, Stalin shamelessly ordered the execution of much of his opposition in a series of purges and show trials. He even executed many older established communists, some apparently just for having contributed more to the revolution than himself. He often replaced these experienced Bolsheviks with inexperienced party members who hadn’t earned their position through merit but through loyalty to Stalin. This further strengthened Stalin’s position within the party, but it also stagnated his organization. Stalin also had tens of thousands of officers purged, which made Russia unnecessarily vulnerable during the Second World War.

Stalin also attempted to erase a number of his opponents from the historical record, including Trotsky. Even works criticizing Trotsky were banned, and he was deleted from photos (see Fig. 592). Some of these doctored photos were so evidently tampered with that some historians believe this was done on purpose, just to show others the state was capable of completely erasing someone from history. The same rudimentary photoshop skills were used to remove the blemishes on Stalin’s face.

The Gulag Archipelago

In an attempt to get rid of the bourgeoisie, Stalin decided to eliminate the prosperous peasants, called kulaks. Hundreds of thousands were arrested and deported. Just earning a little more because of hard work could easily cause a jealous neighbor to declare someone a kulak. Not surprisingly, this method had the effect of weeding out the most effective producers of food from Russia, which was devastating for the food production, leading to famine.

In line with Marxist ideology, the Soviet Union also banned religion, which Marx had called “the opium of the people.” Stalin ordered the destruction of churches and synagogues and executed tens of thousands of clergymen.

Stalin also greatly expanded the gulag system, setting up hundreds of concentration camps across Russia. The system became so large that its forced labor system accounted for an estimated 12–15% of the entire Russian economy. Official archive data has revealed that about 18 million people were sent to the gulag from 1930 to 1953, with 1.5 million dying as a result of their detention.

The writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp and was then exiled for another three years for criticizing Joseph Stalin in a letter to a friend. He later recorded his horrible camp experience in The Gulag Archipelago. He used the word archipelago as a metaphor for the camps, which were scattered throughout Russia like a group of islands. Solzhenitsyn also cynically concluded that the Gulag was actually a microcosm of Russia as a whole, which also functioned as a jail in which people were forced to work.

Historians estimate that about 20 million deaths are directly related to Stalin’s rule (1929–1953). Stalin, however, was not too bothered about this. In a 1947 Washington Post article (naming an anonymous source), we read:

In the days when Stalin was Commissar of Munitions, a meeting was held of the highest ranking Commissars, and the principal matter for discussion was the famine then prevalent in the Ukraine. One official arose and made a speech about this tragedy—the tragedy of having millions of people dying of hunger. He began to enumerate death figures. [...] Stalin interrupted him to say: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” [394]

Fig. 592 – Trotsky (standing on the stairs on the right side of the podium) removed from an image of a speech given by Lenin (1923) (Grigory Goldstein)

Fig. 593 – Nikolai Yezhov, walking next to Stalin, was removed from the photograph after the great purge (1937)

The Five-Year Plan

Stalin turned out to be an even more totalitarian leader than Lenin, aiming to regulate close to everything that happened in the Soviet Union. This was especially true for the economy. In his first Five-Year Plan of 1928, Stalin attempted to organize all production in the Soviet Union, which required hundreds of state personnel at the GOSPLAN to calculate how much production was needed in every sector of the economy. Since this fully impeded Adam Smith’s invisible hand, this led to massive surpluses and shortages. Yet, with massive propaganda campaigns and forced labor, they managed to finish the plan in 1932, one year ahead of schedule. A Second Five-Year Plan started a year later and was also completed ahead of schedule.

In line with Marx’s vision, Stalin abolished independent farms and instead created large collective farms in which peasants worked like factory laborers. Theoretically, the farms were run by all members of the collective, but in reality, a farm manager and a member of the Communist Party were in charge. Collective farms also provided housing, education, medical care, and basic consumer goods and services.

To ensure everyone was behaving according to plan, party members infiltrated every part of society. As a result, everyone felt watched, and it became dangerous to speak one’s mind. A journalist experienced this first-hand when he met a peasant in the presence of his supervisor on his collective farm:

He spoke to me of the successes of the kolkhoz [the collective farm], of the enthusiasm of the country for the collective farm movement, amid of the affection of the peasants for their young Bolshevist leader. This last statement was accompanied by a friendly clap on the back of the president of the Village Soviet. The next morning, however, when far away from any of the Communist members of the kolkhoz, the same peasant, who to all appearance was an enthusiastic supporter of the Soviet power, approached me amid whispered: “It is terrible here in the kolkhoz. We cannot speak or we shall be sent away to Siberia as they sent the others. We are afraid. I had three cows. They took them away and now I only get a crust of bread. It is a thousand times worse now than before the Revolution; 1926 and 1927 were fine years, but now we dare not oppose the Communists or we shall be exiled. We have to keep quiet.” [395]

As Adam Smith had already figured out, farmers generally want to own their own land and reap the economic rewards of their hard labor. Without this incentive, agricultural produce plummeted, leading to chronic food shortages in all parts of Russia. This was most apparent in Ukraine, where Marxist policies led to the Terror Famine of 1932, also known as the Holodomor (meaning “death by hunger”). Stalin had given his troops orders to seize the grain from Ukraine to relieve shortages in other parts of Russia and then close off the area. Estimates put the death toll of this famine between five and seven million. Corpses were littered on the streets, and cannibalism was widespread. Pictures even show people selling human body parts for meat, and some parents were forced to feed their families with the remains of their dead children. Meanwhile, the Russian authorities spread posters stating, “It is a barbaric act to eat your children!” To prevent knowledge of the famine from spreading, movement within the Soviet Union became restricted. The Soviet government also denied reports of the event, and citizens who talked about the famine were imprisoned for three to five years.

In an act of utter stupidity, Stalin also employed the crackpot biologist Trofim Lysenko (1898–1976), which further decreased agricultural production. Lysenko believed that genetic theories were invalid inventions of the bourgeoisie. Instead, he argued for a communist model of agriculture in which different species of plants were grown close together. As a result, most plants died. Another of his theories was deep plowing, which consisted of planting seeds very deep in the soil. Surprisingly, both Stalin and Khrushchev allowed him to retain his position.

Stalin also set out to further the industrialization of Russia, which he managed to do at a phenomenal rate. Factories, plants, mines, and entire industrial cities were built in record times. Whereas in other Western countries, industrialization had taken almost a century, the Soviet Union made the transition in less than 10 years. However, the Russian industry also became known for its inefficiency. For instance, factory workers might be given a quota of delivering, say, 100 turbines a month. To meet this quota in the easiest possible way, they might decide to produce small turbines, even when larger ones were needed. Factory owners also often maintained a surplus labor force, making it easier to reach their targets. As a result, many workers did nothing but were around just in case production needed to be increased at the end of the month. This was the main reason why there was always full employment in the Soviet Union. Similar to cramming for a test, the labor force also had a tendency to procrastinate and rush to meet their targets at the end of the month. Such inefficiencies led to a significant decrease in both productivity and quality. The quota system also discouraged innovation since attempts to try new things were too risky, as failure would prevent factories from reaching their quota.

Some form of money continued to exist in the Soviet Union. Incomes varied according to hours worked and skill level, but even the leaders did not earn much, in line with communist ideals. The money that did exist was of little use because of the shortages and because the Soviet State prioritized industrial goods over consumer products. As a result, a common “joke” among workers became:

We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.

A higher position in the Soviet Union did give access to the best cars, apartments, and stores. This is why Soviet leaders never retired, as it would cause them to lose access to these higher-quality goods and services.

Stalin’s propaganda

Like all of the major dictators of the 20th century, Stalin used film, radio, and photographs as political tools, which had the added advantage of reaching the largely illiterate population of Russia. It was also the perfect medium to show the people the utopia he envisioned for his country, which helped motivate them to contribute to his cause. Radio was an especially popular tool for propaganda. Loudspeakers were placed in houses, factories, and public places and could not be switched off.

Stalin also forbade artists from expressing their individuality and instead demanded that they emphasized collectivity. The artists were told to become “engineers of human souls,” portraying a new type of man and woman who had successfully adopted communist ideals. Art also had to be easy to understand to reach as many people as possible, and it had to be full of praise for Stalin and the Communist Party. The result was art of astonishing banality, far removed from the realities of Soviet life. Any artists who didn’t conform were harshly punished. The poet Osip Mandelstam (1891–1938), who eventually died in prison for criticizing Stalin, wrote:

Only in Russia is poetry respected. It gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder? [396]

Stalin also used film and photography to “update” the past, turning himself into a central character of the revolution as the chief advisor of Lenin. In this way, Stalin created a powerful cult of personality around him. It clearly worked for a lot of people, as evidenced by the thousands of letters of praise he received each month from ordinary citizens. Stalin also deliberately linked himself to Lenin, in order to feed of his popularity. For instance, he changed the name of Petrograd to Leningrad and built a mausoleum in which he placed Lenin’s preserved body.

The Soviets also went to great lengths to indoctrinate the young, especially through an organization called the Young Pioneers. Children were fed stories about role models of good communist behavior. An extreme case was the boy martyr Pavlik Morozov (1918–1932), who, at the age of 14, reported his own father to the government for hoarding, after which he was stabbed to death by his family. The boy was depicted on posters, and even statues were made of him, hoping this would teach children to put loyalty to the state before their own family. Privately, however, Stalin supposedly said about the boy: “What a little pig, who has done something like that to his family.”

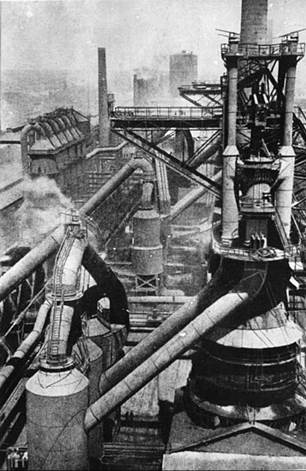

Fig. 594 – Magnitogorsk (Deutsches Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

To convince both the Russians and the rest of the world of their upcoming success, Stalin launched abnormally massive projects. One example is the industrial city called Magnitogorsk (“Magnetic Mountain,” see Fig. 594). It housed the world’s largest power plant, which was deliberately made to exceed its American predecessor. But typical of communist projects, it soon became a “monument to inefficiency.” Another gigantic project that failed was the White Sea Canal. Tens of thousands of gulag workers died during its construction, but when it was finally finished, it turned out to be mostly useless as it had been made too shallow for most boats to sail through, which seems to have been a shortcut to get the project finished on time. Stalin also made designs for a building in Moscow, called the Palace of the Soviets, that was to become taller than the Empire State Building and topped by a gigantic statue of Lenin larger than the Statue of Liberty (see Fig. 595). The building never got beyond its foundations.

Fig. 595 – The Palace of the Soviets, by Boris Iofan (1937)

Useful idiots

The Russian propaganda system also fooled many people outside of Russia. Western journalists friendly to the communist cause were allowed to enter the country, where they partook in staged tours that presented Russia as a communist utopia. Shockingly, some journalists fell for the deception and parroted the Soviet propaganda with great enthusiasm to their audiences back home. In 1932, the British writer George Bernard Shaw called it a “land of hope,” and in 1919, the American journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote:

I have seen the future, and it works! [397]

During the Cold War, these journalists came to be known as useful idiots, who would freely propagandize for the communist cause without fully comprehending what was truly going on. Some journalists even knew better, but nevertheless spread Russian propaganda to retain their access to the Soviet Union.

The Cold War

After the Second World War, the relationship between Russia and the West worsened, especially since the Soviet Union produced a nuclear weapon of its own in 1949. As a result, a tense standoff between Russia and the West followed, known as the Cold War. The most intense moment was the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. The Russians allied with the Cuban communist Fidel Castro (1926–2016) and were allowed to station nuclear missiles on the island, very close to America. This brought the world to the brink of a nuclear war. Fortunately, the prospect of mutual destruction frightened both parties, which caused them to take a few steps back.

Stalin died in March 1953. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971), denounced his crimes but did not give up on communism and was determined to overtake the West in terms of technology. Under his watch, Sputnik was launched, the first artificial satellite to orbit the Earth. Khrushchev also correctly predicted that the Soviet Union would outproduce the United States in concrete, steel, iron, and coal. By the time this happened, however, the United States had moved on to create aluminum alloys, plastics, structural glass, and other advanced technological products.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–2022) became the party’s general secretary. Concerned about the bankruptcy of the Soviet system, he implemented economic reform (perestroika) and allowed constructive criticism (glasnost). In 1991, he signed the documents that officially ended the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Fig. 596 – Part of the Berlin Wall (1986) (Noir, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Berlin Wall

After the Second World War, Germany was partitioned into East and West Germany, with the East coming under Soviet rule. Berlin, situated in East Germany, was also split into two parts, with the Soviets controlling the east side. It was said at the time that if anyone could make communism work, it would be the Germans, but while the capitalist economy of West Germany picked up quickly after the war, the East became a disaster. Whenever West Germans visited friends and family in the East, they were shocked by the number of luxury items that ordinary West Germans could afford. Not surprisingly, many people fled to the West. To further prevent their people from seeing the prosperity of capitalism, the Soviets erected a 7000-kilometer-long barrier made of fences, walls, minefields, and watchtowers to separate East and West Europe. Winston Churchill described it as an “Iron Curtain” that had descended on Europe. The most notable border was the Berlin Wall, which was built in 1961 and fully enclosed West Berlin (see Fig. 597).

To silence any dissenting voices, East Germany established the largest domestic spying network in the world, known as the State Security Police (Stasi). When the Stasi archives opened after the fall of the Soviet Union, it was discovered that about one in seven people had been an informant for the state. Horrifically, it was revealed that even family members had reported on each other.

The Soviets in East Germany also censored artistic expression. Western television, movies, and music were strictly prohibited as they could convince the East Germans of the upsides of the capitalist system. Interestingly, the popular rock and roll music from the West played a significant role in the final collapse of the Berlin Wall. In 1987, David Bowie (1947–2016) gave a concert in West Berlin, close to the wall, allowing thousands of East Germans to listen in. In 1988, Bruce Springsteen (b. 1949) was invited to play in East Berlin, which the communist government had allowed in an attempt to appease the East German youths who were hungry for more freedom. To the crowd, Springsteen said:

I’m not here for or against any government. I’ve come to play rock ‘n’ roll for you in the hope that one day all the barriers will be torn down.

In 1989, after a series of revolutions, the East German government announced that people were allowed to cross the wall. Ordinary Germans then pounded the wall down in celebration.

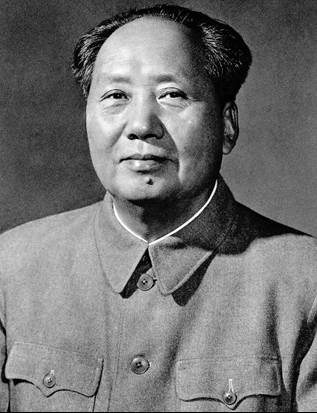

Mao Zedong

China also turned to communism under the leadership of Mao Zedong (1893–1976). Conforming to the Marxist ideal, Mao portrayed rich farmers as oppressors and stirred up the poor to overthrow the government. In 1949, Mao managed to defeat his political opponents and founded the People’s Republic of China. He later admitted to having killed about 800,000 people during the first year of his rule.

In 1953, Mao launched his own Five-Year Plan to collectivize the economy, planning to outdo the Russians. After Stalin’s death, he even claimed to despise the Soviet Union and declared the torch had passed to China.

In 1956, Mao launched his Hundred Flowers Campaign, in which he encouraged citizens to openly express their opinions on the Communist Party, calling for a blossoming of a “hundred flowers and a hundred schools of thought.” Encouraged by this, a large number of people began to speak out, but Mao soon retracted his promise and killed an estimated half-million dissidents.

![]() In 1958, Mao announced the Great Leap Forward, which promised

“hard work for a few years, then a thousand years of happiness.” The government

promised such an abundance of food and clothing that it would be distributed

for free. The hard work was also said to make people healthy, making doctors

unnecessary. But nothing was further from the truth. Combining communist

principles of economics with Lysenko’s agricultural theories, the harvest

failed utterly, creating the greatest famine in world history, causing

an estimated 30 million deaths. As was the case in Ukraine, acts of cannibalism

were recorded. Yet state propaganda kept claiming the new farming strategies were

a success.

In 1958, Mao announced the Great Leap Forward, which promised

“hard work for a few years, then a thousand years of happiness.” The government

promised such an abundance of food and clothing that it would be distributed

for free. The hard work was also said to make people healthy, making doctors

unnecessary. But nothing was further from the truth. Combining communist

principles of economics with Lysenko’s agricultural theories, the harvest

failed utterly, creating the greatest famine in world history, causing

an estimated 30 million deaths. As was the case in Ukraine, acts of cannibalism

were recorded. Yet state propaganda kept claiming the new farming strategies were

a success.

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, which was a campaign to preserve the “true” communist ideology by purging all remnants of capitalism and traditional society. In doing so, millions of people were killed or sent to camps for “reeducation.” During this time, Mao also published his Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, also known as the Little Red Book, which contains statements from his speeches and writings and was presented as a replacement for education. Mao also encouraged young people to report anyone who opposed the communist ideals. Millions of students responded to this call by forming a militant group called the Red Guard. Mao was first supportive of the group, but he later suppressed them with his army as he feared they were getting too strong. Just before his death in 1976, Mao concluded that the revolution was still unfinished and needed to move forward.

After his death, China allowed for a relatively free market, causing the economy to improve, but Mao is still praised by the communist government and his horrible acts have been successfully repressed—one of the starkest examples of historical amnesia in world history.

Fig. 598 – Mao Zedong (1959) (China)

Cambodia and North Korea

Besides Russia and China, many more countries experimented with communism. In fact, at the peak of the Cold War, about a third of the world’s population lived under communist regimes. Take, for instance, Pol Pot (1925–1998) and his communist Khmer Rouge party in Cambodia. Following the Soviet pattern, he too collectivized farms, which led to famine. He also killed over a million dissidents and intellectuals, who were thrown into gravesites known as killing fields.

North Korea is one of the last places where communism still exists today. It turned to communism under the leadership of Kim Il-Sung (1912–1994). Here too, communist ideals led to famine, the liquidation of millions, and barbaric concentration camps, which are estimated to hold a million prisoners. Following the Soviet example, the North Korean regime placed radios in every house to indoctrinate the population and created a personality cult around its leader. The country is also filled with informers, who report to the government. With nuclear weapons and an enormous number of rockets, they continue to pose a threat to surrounding countries.

Like East and West Germany, North and South Korea give us an especially clear comparison between communist and capitalist systems. South Korea is estimated to be 20 times richer than North Korea. The difference can even be seen from space, as South Korea is lit at night, while North Korea is almost completely dark (see Fig. 599).

Fig. 599 – North and South Korea by night

(2012) (Nasa; VIIRS)