An early critic of the Enlightenment was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In a time when most philosophers believed science and reason would bring great progress, Rousseau believed it alienated humanity from its own nature. In his view, life in our tribal days had been much better, especially since primitive man had no knowledge of private property. As humanity became “civilized,” clever individuals amassed enormous wealth and then misused reason to convince the poor of the legitimacy of their station in life, creating great inequality and injustice.

According to Rousseau, there was no turning back to the cave man days, but modern man can still find ways to reconnect with his Nature. According to Rousseau, this meant cherishing one’s own unique feelings, experiences, and potential. Based on this ideal, a new type of hero formed, who dared to live life on his own accord, unfazed by the pressures of mainstream society, and whose subjective experience was rich enough to outshine the cold nature of objective reality.

Music became the most potent vehicle for this new sentiment. Composers such as Beethoven, Berlioz and Wagner took people on a rollercoaster of emotions, ranging from the anticipation of unfulfilled love to the redemptive power of repentance.

Science versus emotion

While the scientific community hailed rationality as the solution to all social ills, another group of thinkers and artists came to believe that the rational approach and the constant progress of science weren’t always for the better. These thinkers ushered in the Romantic Period, which reached its peak between 1800 and 1850. They claimed that a fully rational world view could lead to a cold and banal universe. In the view of the romantic poet John Keats (1795–1821), for instance, Newton had done injustice to humanity by giving a scientific explanation of the rainbow:

Do not all charms fly at the mere touch of cold philosophy? There was an awful [read: awe-inspiring] rainbow once in heaven: we know her woof, her texture; she is given in the dull catalog of common things. Philosophy will clip an angel’s wings. [374]

While Enlightenment philosophers approached every aspect of life through a rational lens, Romantics claimed that many of the most important elements of life have nothing to do with reason. Science tells us little about how we should lead our lives, about our particular emotions and experiences, and about feelings of beauty and mystery that we might experience when we perceive the world. Life, for a large part, is not about objective reality, they claimed, but about the heart.

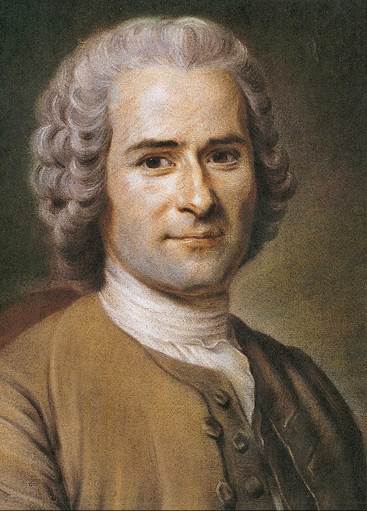

Rousseau

One of the earliest and most important Romantic thinkers was Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), who died about ten years before the start of the French Revolution. In a time when most of his colleagues venerated Reason with a capital “R,” Rousseau claimed it alienated mankind both from nature and itself. An overreliance on reason, he claimed, had not liberated but corrupted our nature.

How did this happen according to Rousseau? Hobbes and Locke had claimed that government had been necessary to protect people from the violence that happened among men in their natural lawless state. Rousseau, instead, romanticized tribal life, stating “nothing is so gentle as man in his primitive state.” [375] This vision of primitive man was during his day already associated with the term “noble savage,” although Rousseau did not use this term. In his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, he claimed our ancestors had been naturally good, and only had casual and infrequent contact. The concept of private property had not yet formed. It was a time “before those dreadful words thine and mine were invented” and before some people craved excessive luxuries while others starved of hunger. As a result, they saw no need to hurt or dominate one another. [376]

Fig. 568 – Portrait of Rousseau, by Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1750-1775) (Musée Antoine-Lécuyer, France)

Then something changed. Rousseau hypothesized that perhaps natural catastrophes brought people into territorial proximity, making property scarce. Being so close to one another, they began to see slight natural differences between themselves, which would have been insignificant in tribal days. Some were stronger, more dexterous, or more eloquent than others. The cleverest and strongest characters must have been able to work the soil better, allowing them to amass more food, and the most eloquent individuals used their clever words to convince others that the soil had become their legitimate property. This, Rousseau claimed, created civilization:

The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, thought up the statement this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him […] was the real founder of civil society. [376]

From observing these differences, the more skilled individuals also developed an artificial amour propre (“love of self”) that made them think better of themselves and made them believe they deserved more than others. This created social hierarchies.

As the opinions of others started to matter, the “savage” who had before “lived within himself,” came to “live in the opinion of others.” [376] As a result, humans also lost their true selves.

As the newly formed elite had their property to lose, they benefited from peace. As a result, they tricked the poor into giving up their right to their share of the property in exchange for protection by a government. This, Rousseau claimed, was the government that Locke and Hobbes had defended. Locke had been right that government was instated to protect private property, but this was not a good, but a hoax perpetrated by the rich on the poor to institutionalize economic inequality, which became the source of endless strife. Government had not helped humanity, but had instead introduced and legitimized the introduction of vice into the world. Government had not prevented Hobbes’s state of nature, but had caused it. But since the terms of government seemed so sensible—ensuring the security of all subjects—“all ran headlong to their chains, believing they had secured their liberty.” As a result, the lower classes were “groaning under an iron yoke, the whole of humanity crushed by a handful of oppressors” who “held sway over the weak, armed with the formidable strength of the law.” [376]

The endless strife, he continued, made government unsustainable in the long run. As a result, he predicted “we are approaching a state of crisis and the age of revolutions.” He added: “I hold it to be impossible that the great monarchies of Europe still have long to survive.” Although he never advocated for revolution himself—believing it to cause more problems than it solved—his philosophy would become one of the main sources of inspiration behind the French Revolution.

It might come as a surprise that Rousseau was initially on good terms with some of the major Enlightenment philosophers of his day. For instance, he became good friends with Diderot, for whom he wrote the entries on political economy and music in his Encyclopedie. He even visited Diderot daily when he was imprisoned and implored the authorities to release him. But as his deep skepticism toward the Enlightenment project intensified, his colleagues began to see him as a traitor to their cause.

The Social Contract

Although critical of modern life, Rousseau didn’t believe there was a viable way back to primitive days. He also did not wish to abolish people’s ability to acquire property through their own labor, as this would only increase the power of the state, as it would need the authority to confiscate property. However, he did believe great improvements could be made. For instance, we could educate our children differently, which he discussed in his book Emile. It was somewhat ironic that Rousseau wrote a book on education, as he had abandoned all five of his children to a public orphanage, but the book made an interesting case. While Locke believed that children should be molded early on to instill in them liberal ideals, Rousseau believed children should be allowed to develop naturally at their own pace and without overbearing adult expectations.

He also believed there was a way to improve government, which he discussed in his work The Social Contract (a term he coined). The work starts with his most famous line:

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. [376]

In this work, Rousseau recommended a government based on liberty and equality, in which all subjects gave up an equal amount of freedom and in which all subjects were equally sovereign, allowing no one to gain authority over another. According to Rousseau, this required all citizens to participate by voting on legislation.

Rousseau also advocated for religious tolerance, as long as people believed in an omnipotent, intelligent, and beneficent divinity, as he deemed this necessary for the stability of government. People should also swear an oath in which they agreed to respect the sanctity of the Social Contract. Anyone who betrayed this oath, he claimed, should receive the death penalty.

The Solitary Walker

Besides criticizing his contemporaries, Rousseau also developed an alternative philosophy of life that would inspire the development of the Romantic period in the century after his death. Important to his philosophy of life was his love for Nature, which he capitalized because he considered it divine. Rousseau often stood before nature in deep awe, seeing in it the work of the Creator. It was remarkable to him that people ever needed rituals or a sacred book with revelations, while they could also immerse themselves in Nature. In contrast, traditional religion led people to dominate one another, placing biblical authors and a priestly class between God and the believer:

I would rather have heard God himself. […] So many men between God and me. [376]

Confronted by Nature, especially our own nature, including our heart and our conscience, no artificial religion was needed.

He expressed his love for Nature most beautifully in The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, which would become highly influential among later Romantics. Rousseau wrote this work near the end of his life at a time when his Enlightenment friends had abandoned him and when his critique of Christianity got his work banned, making him a fugitive from justice. He had to travel incognito, and at some point, villagers threw rocks at a house he was staying in. Overwhelmed by all this, he became paranoid. He could only find respite in solitude during his walks in Nature, which filled him with ecstasy and purified his mind.

In this work, we follow him during a series of ten walks where he reminisced about nature and the important experiences of his life. We read of the pleasure he felt naming the plants still in flower in the meadows and of a mountain gorge, where he found various plants, heard the cries of an owl and an eagle, and then sat down on pillows of lycopodium, believing he had found a hidden corner of the Earth, where his persecutors would never find him. On another walk, he recollected seeking refuge on an island in a lake in Switzerland, where he “would have been content to live all my life, without a moment’s desire for any other state.” At times, he would lay outstretched in a boat, drifting wherever the waters took him, “plunged in a thousand indistinct and yet delightful reveries.” [376] At other times, however, Rousseau drifted into deep despair, insisting that all our plans for happiness are mere fantasy.

During another walk, he reminisced about how his love for an older married woman had shaped him when he was still a young man. He had been only 15 years old when the 29-year-old Swiss baroness Madame de Warens took him into her home to become his tutor in philosophy and literature, but soon they also became lovers. During the walk, it had been exactly 50 years since they first met. He remembered their time together as a period in his life in which he had been utterly himself. We read:

I recall with joy and tenderness this unique and brief time of my life when I was myself, fully, without admixture and without obstacle, and when I can genuinely say that I lived. […] Without this short but precious time I would perhaps have remained uncertain about myself. […] I would have difficulty unraveling what there is of my own in my own conduct. [377]

Rarely in world history up to his day, do we find someone discussing his subjective experiences and emotions with such uncompromising openness and vulnerability.

Julie and the Confessions

This emphasis on the inner world can also be found in his work Julie, or the New Heloise, which became the most popular work of fiction of the late 18th century. The story tells of a young woman of noble birth named Julie, who falls in love with her tutor Saint-Preux, yet was engaged to be married to someone else. When she eventually did marry, she fell into a deep depression and even died, unable to bear the pain of living without Saint Preux. His point was—and this is again a key insight of the Romantic period—that we better follow our deepest motivations, for denying them can come at a significant cost—it can alienate us from ourselves.

When writing Julie, Rousseau was himself in love with a married woman named Sophie d’Houdetot, who did not reciprocate his feelings. In a number of letters to her which he never sent, he described his love for her in terms that convey the intensity of his feelings and the richness of his inner world—we read of “involuntary excitement,” “sublime frenzy,” “sacred fire,” “noble delirium,” and so on. [376] In his Confessions, which we will discuss shortly, he also tells us how he got so infatuated thinking about Sophie that his knees grew weak. In a moment of remarkable honesty, he admitted he then ejaculated to diffuse the buildup of tension in his body.

Rousseau wrote his Confessions in 1769, but the work was published only after his death (although he did read excerpts publicly in the salons of Paris). The title of the work was a direct reference to the Confessions of Augustine, who also searched his “inner self,” including his darkest secrets. But while Augustine wrote his autobiography to help others along their religious path, Rousseau’s main purpose was “to contribute to an accurate knowledge of my inner being in all the different situations of my life.” Rousseau believed that everything about himself was important and needed to be shared with the world, both his good and his scandalous deeds, presenting himself as a “singular soul, strange, and to say it all, a man of paradoxes.” [378] According to Rousseau, his internal world was both original and interesting in itself, two Romantic ideals.

Also in contrast with Augustine, who journeyed inside of himself to find God, Rousseau hoped to discover and express his own unique hidden motives. These motives, he claimed, have to come to consciousness if we wish to live authentically, in line with our true selves. This self, he added, was not the rational or even moral self, but the self that exists in the world of our feelings and memories. Especially love, he believed, can give a man “new reasons to be himself.” [231] At the start of the Confessions, Rousseau clearly sets out this goal:

I have begun on a work which is without precedent, whose accomplishment will have no imitator. I propose to set before my fellow-mortals a man in all the truth of nature; and this man shall be myself.

I have studied mankind and know my heart; I am not made like anyone I have been acquainted with, perhaps like no one in existence; if not better, I at least claim originality, and whether Nature has acted rightly or wrongly in destroying the mold in which she cast me, can only be decided after I have been read.

I will present myself, whenever the last trumpet shall sound, before the Sovereign Judge with this book in my hand, and loudly proclaim, “Thus have I acted; these were my thoughts; such was I. With equal freedom and veracity have I related what was laudable or wicked, I have concealed no crimes, added no virtues; […] Such as I was, I have declared myself; sometimes vile and despicable, at others, virtuous, generous, and sublime; even as Thou hast read my inmost soul: Power eternal! Assemble round Thy throne an innumerable throng of my fellow-mortals, let them listen to my confessions, let them blush at my depravity, let them tremble at my sufferings; let each in his turn expose with equal sincerity the failings, the wanderings of his heart, and if he dare, aver, I was better than that man.” [379]

Among his many flaws, he then tells us how being beaten by a nanny as a child aroused sexual feelings in him, he tells of his habits of masturbation, his flawed relationships with women, and his abandonment of his children. This, however, was not an act of pure humility and self-deprecation, but instead an honest account of the flaws that even a generally good person might have. It needed to be included if he was to present a full picture of himself to the world.

The Transcendentalists

The greatest American Romantics, known as the Transcendentalists, were Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). Both of these writers encouraged people to think for themselves, instead of mindlessly going with the crowd. In his famous work called Self-Reliance, Emerson wrote:

It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of a crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude. [345]

For Emerson, to think for himself also meant distancing himself from his European roots, and daring to stand on his own feet as an American:

We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe. We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak with our own words. [345]

Both Emerson and Thoreau rejected traditional religion, which they considered stiff and outdated. Similar to Rousseau, they instead sought divinity in nature. To them, nature was a form of poetry, a living Bible that has the power to heal the soul.

Thoreau, who was Emerson’s younger friend and neighbor, had an uncompromising character and forcefully chose to live his life according to his own standards:

If a man does not keep pace with his companions perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. [345]

He not only rebelled against tradition and religion, but even against unnecessarily strict laws. In his essay Civil Disobedience (1849), which would later inspire Martin Luther King, he wrote:

If the law is of such a nature that it requires you to be an agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. [345]

It was for this reason that he opposed slavery and applauded those who worked to undermine it. Disgusted by his government’s involvement in the American-Mexican War, he even refused to pay taxes, for which he was put in jail (but only for one night, as his aunt agreed to pay the taxes for him).

Thoreau also cared little for material goods and wealth, preferring a simpler life. To live in accordance with this ideal, he moved to the woods at the age of 27, where he lived for over two years in a tiny, one-room cabin at Walden Pond. He wrote about his experiences there in Walden¸ Life in the Woods (1854), which is another quintessential work in the Romantic tradition.

The Romantic hero

Romantic artists translated these ideas into music, art, and literature. The free expression of feelings came to take center stage. Even the formal rules of the various artforms were thrown aside where they impeded self-expression. It was believed that nothing should impede the imagination of the artist. Unthinkable in other times, writers wrote openly about their difficult feelings and insecurities, which came to be seen as an act of bravery and a moral virtue in and of itself. Romantic artists also made originality and authenticity a virtue. In earlier times, artists generally presented their work as part of an established tradition. Medieval writers, for instance, often went to great lengths to convince their readers that their material was not original, but was, in fact, the most accurate version of an ancient story. Even Newton had claimed that Pythagoras must have already known about his inverse square law, instead of claiming the discovery for himself.

Romantic writers also defined a new type of hero. This character was often a genius, striving to follow his own unique life’s path, even when this led him to be rejected by society. In line with this, the hero was often a strong introvert, placing his subjective experience of the world above objective reality. In great contrast to the classical heroes, who are known for their strength and confidence, these characters were often haunted by feelings of loneliness, melancholy, alienation, regret, self-criticism, lovesickness, and even thoughts of suicide. A typical example of this hero is a character named Werther from The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Goethe (1748–1832), who was described as a lonely and tormented man and who ultimately failed in his quest for love and committed suicide.

Fig. 569 – Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich (1818) (Cybershot800i; Kunsthalle Hamburg)

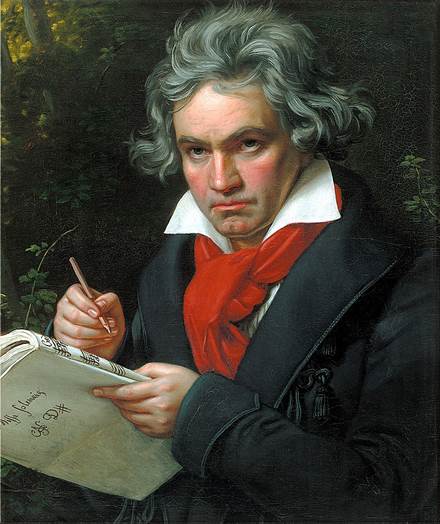

Music

Whereas the Renaissance can be best understood by studying the visual arts and the Enlightenment by studying science, music was considered “the most romantic art.” Intellectuals and artists alike lauded music for its ability, more than any other artform, to induce strong emotions. Music can work on the mind most directly, sweeping us off our feet. This was also the opinion of Rousseau, who was himself an admired composer. The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) agreed, believing that only music could express the full range of human emotion. He explained:

Instrumental music is entirely independent of the phenomenal, that is, the conscious, everyday world. It ignores it altogether. It is a copy of the will, the great inner truth itself. That is why the effect of instrumental music is so much more powerful and penetrating than that of the other arts. It expresses the essence behind appearance. Thus, the creator of [instrumental] music reveals the inner truth of the world. [380]

Like the ideal romantic hero, Romantic musicians saw themselves as beholden to nobody but themselves, except perhaps to their muse. In their view, God had endowed them with genius, a gift, or a vision, which had to be nurtured at all costs.

Fig. 570 – Portrait of Beethoven, by Karl Joseph Stieler (1820)

Romantic music started with Beethoven (1770–1827). Although he started out as a classical composer, he eventually let go the strict conventions of Classicism in favor of self-expression, which allowed him to channel his rage, alienation, passion, and imagination into music. Since the Renaissance, musicians had already attempted to convey the emotions of the lyrics they sang, but what Beethoven did was new. He began to express his own emotions. His most famous work, perhaps the most famous piece of music of all time, is his Symphony No. 5, which starts with his dark and ominous fate motive—“dot-dot-dot-dash.” According to his first biographer, it sounded like the hand of fate was knocking on his door (although Beethoven himself claimed it was inspired by a birdsong). Revolutionary for its time, the piece doesn’t seem to follow any clear rules, but instead served mainly as a means to self-expression, allowing him to channel his rage. As a result, the work is wildly original. The 5th symphony can’t really be compared to anything else. Beethoven’s fifth only sounds like Beethoven’s fifth.

Another typical work of the Romantic era is Symphonie Fantastique by the French composer Hector Berlioz (1803–1869). It tells the story of a young man hopelessly in love with a woman who did not return his feelings—clearly a romantic motif. The piece then takes us on an emotional rollercoaster characteristic of the romantic era, which is worth exploring in some detail.

The symphony revolves around a short tune expressing longing, which Berlioz called his idee fixe (fixed idea). The tune rises, giving a feeling of hope, but then drops before reaching its peak. Whenever the girl he is in love with, or the mere thought of her, appears in the storyline, we hear the idee fixe in one way or another. In the first movement, called Reveries and Passions, the idee fixe appears “noble and shy,” creating in the hero (and thus the listener) a sense of longing, anticipation, and heartache. In the second movement, called A Ball, the hero is dancing an uplifting waltz in a crowded room, but gets distracted on various occasions by thoughts of his girl. Each time this happens, the waltz quiets down and we again hear the idee fixe. According to Berlioz, “The beloved image keeps haunting him and throws his spirit into confusion.” [381] In the third movement, called Scene in the Country, turbulent music is meant to convey a storm, which represents the storm of his heart, and ends on a depressive note as the hero decides there is no hope for him. In the fourth movement, called March to the Scaffold, the hero has given up and overdoses on opium. He then hallucinates he has murdered his beloved and will be executed as punishment:

Convinced that his love is unappreciated, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of the narcotic, too weak to kill him, plunges him into a sleep accompanied by the most horrible visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved and he is condemned and led to the scaffold and that he is witnessing his own execution. The procession moves forward to the sounds of a march that is now somber and fierce, now brilliant and solemn, in which the muffled noise of heavy steps gives way, without transition, to the noisiest clamor. At the end of the march, the first four measures of the idée fixe appear like a last thought of love, interrupted by the fatal blow. [381]

The movement ends with his head cut off by the guillotine, followed by three descending plucked notes depicting his head falling into the basket. Then we hear a drumroll and brass fanfare that celebrates the death of the artist.

In the fifth and final movement, called Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath, the piece becomes even more bizarre. His girl has joined a group of monsters who are dancing in celebration at the young man’s funeral:

He sees himself at a witches’ sabbath, in the midst of a hideous gathering of shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind who have come together for his funeral. Strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter; distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts. The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque: it is she who is coming to the sabbath… Roar of delight at her arrival… She joins the diabolical orgy [381]

Fig. 571 – Photo of Wagner, by Franz Hanfstaengl (1871)

The idee fixe is now presented by a shrill squeaky clarinet and his beloved is portrayed as an old hag who dances to an obscene tune that parodies the famous medieval Dies Irae plainchant by Thomas Celano (c. 1185–1265), a tune commonly used to describe the souls coming before the throne of God during the Last Judgment.

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) took romantic music to the next level. In many of his opera’s, such as Tannhauser, he, although himself an atheist, purposefully hijacked the power of religion to create a maximally transformative experience for his audience, lifting them to spiritual heights. In Tannhauser, he uses the Christian ideal of redemption through penance. No matter how corrupted we have become through our mistakes in life, the Christian faith tells us, God will redeem those truly repentant. In the story, a minstrel named Tannhauser cheated on his future wife Elizabeth with the goddess Venus, whom he had enticed with his beautiful music. Over time, Tannhauser grew weary of the indulgent existence with Venus, no matter how perfect, and longed to return home. Back home, when the men of the city discovered he had been with Venus, they attempted to kill him, but he was finally granted the opportunity to travel to Rome with a group of pilgrims as repentance and as an attempt to obtain a pardon from the pope. When the pilgrims returned, Tannhauser was not among them. Overcome with sorrow, she fell to her knees and sang a prayer to the Virgin, begging to trade her life for Tannhauser’s redemption. In rapture, she then ascended to heaven. We then learn that the pope had refused to grant him forgiveness, which drove Tannhauser to despair. The pope told him he was “forever damned.” Just as my staff will not bear fresh leaves, the pope told him, salvation would never come to him. Crushed by the news, he called out to Venus to take him back, who welcomed him. Then he heard a funeral hymn and realized Elizabeth had died. This brough him such great emotion that Venus knew she had lost him. Tannhauser bent over Elizabeth’s body and died from despair. As a glowing light bathed the scene, a group of pilgrims arrived, singing one of Wagner’s greatest compositions. They had come to bring the pope’s staff, which was sprouting new leaves. They then proclaimed a miracle had happened and sang of the power of redemption:

Redemption has been granted to the world. In a sacred hour of the night, the Lord revealed Himself through a miracle: He adorned the withered staff in the priest’s hand with fresh greenery. Thus, to the sinner in the flames of hell, shall salvation blossom anew! […] God reigns high above the whole world, and His compassion is never sought in vain! Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah! The Holy Grace of God is given to the penitent, who now enters into the joy of Heaven!

Wagner also drew heavily on mythological symbols and archetypes, which he knew resonate with people on a very primal level and gave the audience easy access to a whole range of universal human emotions. For instance, in his opera called The Ring of the Nibelung, he capitalized on Germanic myth, speaking directly to the primordial parts of his German audience (which Hitler would later exploit to fuel sentiments of German nationalism among his supporters). The first part of the opera, called The Rhine Gold, starts with a dwarf named Alberich who managed to steal gold from maidens who live at the bottom of the Rhine, which he presents as a primordial German river.

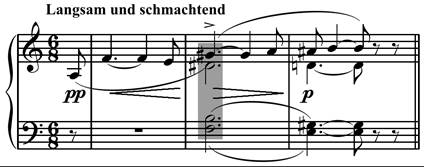

In his opera Tristan and Isolde, he followed the medieval writer Gottfried von Strassburg in presenting earthly love as divine. In the first few seconds of the piece, Wagner introduced his famous Tristan chord, which the ear perceives as unresolved. This creates a tension in the listener that causes a yearning for the chord to be resolved, which feels somewhat similar to the yearning of separated lovers. Wagner cleverly captured the bittersweet quality of lovesickness by presenting the chord as a clever conjunction linking a number of downward notes (depression) with a number of upward notes (hope).

Fig. 572 – The Tristan Chord is depicted in the grew box

Instead of giving the desired resolution, Wagner moved from one unresolved chord to the next. On many occasions, he gives his listener the impression that the desired resolution is imminent, only to just miss it. Wagner himself described his masterwork as follows:

Henceforth no end to the yearning, longing, rapture, and misery of love: world, power, fame, honor, chivalry, loyalty, and friendship, scattered like an insubstantial dream; one thing alone left living: longing, longing unquenchable, desire forever renewing itself, craving and languishing; one sole redemption: death, cessation of being, the sleep that knows no waking! [382]

The long-awaited completion finally comes at the very end, after almost four hours of opera, when Isolde dies out of love upon finding Tristan’s body, which Wagner referred to as the Liebestod (“Love Death”).