In the city of Athens, a new form of politics emerged that would become one of the cornerstones of Western civilization. We are talking, of course, about democracy, which literally means “the rule of the people.” Athenian democracy transferred power from the elites to all male citizens, both the rich and the poor. In its final form, these citizens took turns to vote directly on all important decisions of the city, such as the acceptance of new laws, the outcome of trials, and the spending of public money.

The route to democracy took various centuries to complete, which speaks to the enormous dedication of the Athenians to figure out how to make this new system work. Many Athenians were proud of their achievement and felt they were setting an example for other cities to follow. Others, however, were not so happy about democracy. Many intellectuals of the time warned that the rule of the people also meant the rule of the stupid and the uninformed.

The development of democracy in Greece is just one aspect of a groundbreaking trend among the Greeks of an increased trust in the capabilities of mankind. We will begin this chapter by discussing this topic.

An appreciation for mankind

During the Classical Period, some Greeks started to develop a new vision of man that would become a hallmark of Western thought. They began to see men not only as pawns pushed around by divine forces but as individuals with their own sense of agency. The Greeks gained trust in their own abilities and, as a result, began to cultivate an unprecedented appreciation for humanity.

We have already witnessed this new attitude in the increased faith of the Greek philosophers in their ability to understand the universe. Similarly, the Greeks had great trust in their physical abilities. They proudly showed off their excellence in many athletic competitions, such as the Olympic Games. In these competitions, individuals strove to become the best at their particular sport and achieve lasting glory.

Fig. 312 – The punishment of Prometheus (Poggemann, CC BY 2.0; Vatican Museum)

Greek mythology also showed evidence of this new way of thinking. Even though the Greek myths often refer to gods and spirits, the loyalty and sympathy of the Greeks was regularly on the side of man. To illustrate this, the mythologist Joseph Campbell compared the Jewish story of Job to the Greek story of Prometheus. Job was a successful and God-loving man, yet one day, God was tempted by the devil to bring many hardships on him to test his faith. God took away his property, his friends, his family, and his health. At the end of the story, God appeared before Job. Instead of justifying his actions, God emphasized Job’s inferiority and his inability to understand the will of God. Job concluded, “I am unworthy” and “I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes.” Joseph Campbell wrote:

Never do we hear from the Greek side any such fundamental betrayal of the human cause as is normal and even required in the Levant. [60]

Fig. 313 – Kouros youth (c. 600 BC) (The MET)

Fig. 314 – Kritios boy (c. 480 BC) (Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 3.0; Acropolis Museum)

![]()

![]()

In contrast, in the play Prometheus Bound, often

attributed to Aeschylus (c. 525–455 BC)¸ the titan Prometheus stole

fire from the gods for the benefit of mankind and also thwarted a plan

by Zeus to obliterate the human race. When Zeus found out what had happened, he

ordered Prometheus to capitulate. However, Prometheus stood by his judgment and

responded:

I care less than nothing for Zeus. Let him do as he likes. [134]

Zeus then condemned Prometheus to eternal punishment, chaining him to a rock where his liver was eaten daily by an eagle, only to be regenerated by night due to his immortality (see Fig. 312).

In Prometheus Unbound, the second part of the play, of which only fragments remain, Heracles freed Prometheus from his chains and killed the eagle. In the last part, Prometheus the Fire-Bringer, Prometheus warned Zeus not to sleep with the sea nymph Thetis, for she was fated to give birth to a son greater than his father. Wanting to retain his place as king of the gods, Zeus decided to marry Thetis off to the mortal Peleus. Their child would become the mighty Achilles. Grateful for the warning, Zeus finally reconciled with Prometheus.

Greek sculptors also gave expression to the new individualistic approach. In their works, they displayed an unprecedented appreciation for and knowledge of the human body. This development is clearly depicted in Fig. 313 and Fig. 314. On the left side, we see a sculpture from the Archaic Period of Greece (from around 600 BC). The style here is still clearly inspired by Egyptian art. Notice the simplistic treatment of the body and how no attempt was made to turn this character into an individual. The character is not a unique person but a stereotype. The sculpture on the right is the famous Kritios Boy from about 480 BC. Here we suddenly see a lot more attention to detail and a much more dynamic and natural body. Notice, for instance, how the hips are slightly tilted, making one leg carry more weight than the other (a pose called contrapposto). The body was also masterfully sculpted to give the feel that muscles lie beneath the surface of the marble’s skin.

Fig. 315 shows a sculpture from about the same time. Notice the extraordinary advances toward naturalism that were made. Also notice that this person is no longer staring aimlessly in the distance but is looking at the ground, suggesting introspection and emotion. We can feel the suffering of this fallen hero.

The rule of the people

The new increased concern for mankind also expressed itself in the creation of the Athenian democracy. Although democratic institutions existed before—we have some evidence of voting and popular assemblies from the early days of Mesopotamia—the Greek attempt surpassed all its predecessors, investing an unprecedented trust in the decision-making of ordinary citizens. As the historian Kurt Raaflaub wrote:

No [city-state] had ever dared to give its citizens equal political rights, regardless of their descent, wealth, social standing, education, personal qualities, and any other factors that usually determined status in a community. [135]

Early Athens

Originally Athens was a monarchy, ruled by a basileus (a king) who held his office for life. Possibly in 682, Athens turned into an oligarchy, with the basileus being replaced by three archons (meaning “one who rules”). Later in the century, the number of archons was extended to nine. Archons were elected every year from among the aristocracy by the council of ex-archons, the Areopagus, which the Athenians believed had been instituted by the gods.

Greece also had a long history of popular assemblies, dating back to at least the late eighth century, as they are described in both the Iliad and the Odyssey. In Homer’s descriptions, even commoners were allowed to get their voices heard.

In 621 BC, the demand for a fairer and more accountable government inspired the creation of a written code of law that was displayed in public. As a result, political power could no longer be exerted arbitrarily but had to be applied indifferently to all members of the community. The first written code of Athens was drawn up by Draco. Very little is known about him or his legislation, but we know that his laws were severe to the extreme. According to Plutarch (46–120 AD):

Draco assigned one penalty to almost all crimes; capital punishment, so much so that even those guilty of idleness were sentenced to death, and those who had stolen some vegetables or fruits received the same punishment as the criminals guilty of sacrilege or murder. [...] Draco himself, as they say, when he was asked why he had assigned the death penalty for most crimes, answered that capital punishment was, in his opinion, an adequate penalty for the smaller crimes, but he could not find a heavier punishment for the more serious ones. [124]

At the time, the land around Athens was owned by a few rich families, and the poor farmed their land for rent. When unable to pay this rent, these farmers became debt-slaves. On top of this, the poor had no political representation. The direness of this situation is described in an anonymous document titled The Constitution of the Athenians (c. 325 BC), which might have been written by one of Aristotle’s students:

The constitution was oligarchic in every respect and the people of the poorer classes, men, women, and children, were enslaved to the wealthy. […] The most grievous and intolerable aspect of the constitution of the time for the populace was their state of serfdom, but they were annoyed with everything else as well, because they had no share in anything at all. [124]

As these problems persisted, the social tensions between the rich and the poor grew larger and larger. On top of this, the city was plagued by different clans pushing for power, which often led to anarchy and conflict. Something had to change.

Solon

Reform finally came when a man named Solon was elected archon in 594 BC. The Constitution of the Athenians refers to him as “the first to champion the people.” He stood out as an unbiased and respected personality who had not been involved in party strife. Plutarch wrote about him:

The most reasonable men among the Athenians cast their eyes on Solon as the only man who was not implicated in the errors of the time, for he was neither associated with the arrogance of the wealthy nor was he held fast to the constraints of the poor. Therefore they implored him to come forward publicly and put an end to the strife. [124]

Solon knew he had to find a balance between the contradicting demands of both the rich and the poor. This meant he had to find a compromise. We read:

I have given the people as much power as was sufficient; I have not deprived them of their dignity nor given too much. Those who had power and splendid wealth, I made sure that they would not suffer harm either. I stood up between them, holding a mighty shield, and let neither party triumph unjustly. [124]

The wealthy, however, did have to surrender some of their wealth and power to resolve the problems of Athens:

[Solon urged] the wealthy not to be contemptuous: “You, who are plunged with so many goods, calm down the strong passions of your heart and put a limit to your vast ambition; we won’t bow down, nor will you have everything at your will.” [124]

One of Solon’s radical decisions was to cancel all debts and make debt-slavery illegal, making Athenians, by definition, free. He also ensured that land was distributed more fairly. We read:

Once he became master of the situation, Solon set the people free for the present and for the future, and banned the loans guaranteed on the debtor’s person, and established laws and ratified cancellations of public and private debts. These measures were called “the shaking-off of burdens,” for people had shaken off a heavy load from their shoulders. [124]

Solon also attempted to weaken the rule of the aristocrats by replacing the old social hierarchy with four new property classes. People in the highest two classes were eligible for important magistracies, including archonship. As these new classes were based on wealth rather than birth, it helped dilute the aristocracy, giving anyone who amassed enough wealth a chance to attain political power. Members of the poorest class were not eligible for any magistracy, but they did have the right to serve as jurors in the law-court and sit at the ekklesia (the assembly). Some sources also credit Solon with the introduction of the boule, which was a branch of government that set the agenda of the assembly and had 400 members.

Solon was clearly happy with the results of his reforms. We read:

Many who had been sold off as slaves, [...] I have brought them back to god-built Attica, their fatherland. I set free those whom dire necessity had made exiles [...] and those who had endured dire slavery here, and were trembling before their masters. [...] I have written laws that apply equally to the commoners and the well-born. [...] If another man, foolish and ravenous, had taken the ox-goad instead of me, he would have been unable to hold back the people. If I had been obliged to the interests of one faction, and then to any countermeasure of the other, the city would have been bereaved of many men. For this reason, I have stood on guard on every side. [124]

After his term, Solon gave up his power and left the city for ten years. He made the Athenians promise to respect his reforms, but this promise was not kept for long:

On the fifth year since the archonship of Solon, the Athenians were unable to elect the archon owing to the political divisions. Four years later, the Athenians did not appoint the archon for the same reason. After these events, the same period of time having elapsed, Damasias was elected archon and held the post for two years and two months until he was removed from office by force. [...] The Athenians were in a perpetual state of strife. For some of them, the main reason for discontent was the cancellation of debts, which they claimed had reduced them to poverty; others were dissatisfied with the present state of the constitution, because it had been [...] modified; for some, the only reason was mutual rivalry. [124]

Pisistratus

In 561 BC, after a period of chaos and anarchy, Pisistratus took control of Athens. Being a tyrant, he established his position by resorting to violence, yet after gaining control, he became a mild ruler, often “pursuing the common interest” of the people. He even kept Solon’s laws in place, did not suspend the government, and continued to allow elections for various positions. Today the word “tyrant” (“one who takes power by force”) has a negative connotation, but in Greece, it was a neutral term. In fact, Pisistratus brought a much-needed period of peace and stability to Athens.

Pisistratus also made a host of changes beneficial to Athens. In rural areas, he instituted local tribunals, allowing poor farmers to benefit from the political institutions of the city without having to leave their farms. He also offered loans to the poor at low interest and instated a 10% tax on agricultural produce. With all these changes, he made Athens the center of trade in Greece and transformed it from a group of warring clans into a state with a strong, unified identity. He also initiated an impressive building program and created festivals that also made Athens the cultural center of Greece.

When Pisistratus died in 528 BC, power passed to his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. Hipparchus was assassinated, after which the rule of Hippias became harsher. It didn’t take long before the Athenians wanted him removed.

Cleisthenes

With help from the Spartans, an Athenian named Cleisthenes overthrew the tyranny of Hippias and banished him from the city. After some internal strife, Cleisthenes assumed leadership of Athens in 509 BC. He became a great reformer, turning Athens into a democracy. He called his reform isonomia (“equality before the law”), which set out to involve all male citizens in the political affairs of Athens. To accomplish this, he divided Athens into ten tribes. He divided Athens into small units assigned to the city, the coast, or the rural inland. Three units, one from each region, were then selected by lot and combined to form one tribe. In this way, every tribe contained a broad cross-section of the population and could fairly represent the entire city.

The new tribes became the basic units for the military, political, and administrative organization of Athens. The tribes, for instance, had to contribute to the new boule, which had the purpose of supervising and preparing the agenda for the assembly. Under Cleisthenes, the boule was reorganized to include 500 members, 50 from each tribe, who were chosen by lot and replaced annually. Each tribe represented the entire city for one month a year. Every day at sunset, a lot was drawn to appoint the president of that day. Every citizen could serve on the boule twice in his lifetime, but not in consecutive years. As a result, every Athenian male was likely to serve in the boule at least once in his life.

Cleisthenes also placed the running of the state into the hands of the assembly, allowing it to propose and vote on laws, appoint magistrates, and judge various trials. It was summoned at least once per month, and meetings lasted all day. To make the assembly maximally effective, Cleisthenes introduced isegoria (“equal speech”), giving every male citizen the right to address the assembly (the assembly started each session with the words: “who wishes to speak?”). The historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BC) remarked that under tyranny Athens had been unremarkable, but this all changed when they introduced equal speech:

This makes it clear that free and equal speech (isegorie) is a serious thing not only in one respect but in all, if the Athenians under tyranny were weaker in warfare than their neighbors, but having thrown off the yoke were first by far. This shows that, held down by authority, they shirked their duty in the field, because they were working for a master, but once free each man was eager to work for himself. [136]

The tragic writer Euripides (c. 480–406 BC) endorsed free speech in his play Suppliant Women, writing: “This is true Liberty when free born men, having to advise the public may speak free. […] What can be more just in a state than this?” [136]

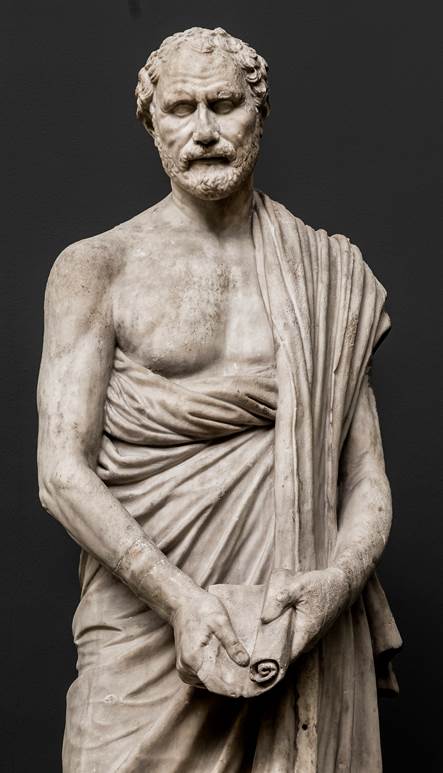

Fig. 316 – Statue of the famous orator Demosthenes (3rd century BC) (Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 4.0; Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, Denmark)

The famous Athenian orator Demosthenes (384–322 BC) in his speech Against Leptines, noted with pride that the Athenians were allowed to criticize their own constitution and praise the Spartan one, while Spartans could only praise their own. To this, day, critique of one’s own government is an important litmus test to distinguish a totalitarian regime from a true democracy.

In practice, however, only skilled speakers dared to speak since the Athenians were very critical when anyone spoke outside of his expertise. In one of Plato’s works, we read:

When the Athenian assembly discusses construction, the citizens call for builders to speak, and when it discusses the construction of ships they call for shipbuilders, but if anyone else, whom the people do not regard as a craftsman, attempts to advise them, no matter how handsome and wealthy and well-born he may be, not one of these things induces them to accept him; they merely laugh him to scorn and shout him down, until either the speaker retires from his attempt, overborne by the clamor, or the archers pull him from his place or turn him out altogether by order of the presiding officials. [137]

Yet, when the discussion was not about technical matters but about the governing of the city, “the man who rises to advise them on this may equally well be a smith, a shoemaker, a merchant, a sea-captain, a rich man, a poor man, of good family or of none.” [137]

The speakers also had to train to project their voices since, generally, thousands of Athenians would show up and the discussions were often quite tumultuous. Demosthenes, for example, practiced speaking over the sound of the ocean waves to improve his projection.

Besides Isegoria, the Athenians also recognized parrhesia (“uninhibited speech”), which allowed citizens to express their opinions even outside the assembly. Especially philosophers and playwrights took advantage of this freedom.

There were only a few restrictions on speech, including defamation (kakegoria) and impiety (asebia), the latter being punishable by death (as had happened to Socrates). It was also forbidden to profane the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secretive initiation rite surrounding the cult of the goddess Demeter. Overall, however, speech was generally free, allowing for the avalanche of great ideas that have brought great progress to humanity.

The court under Cleisthenes also became directly controlled by the people. It was composed of 6000 jurors selected by lot at the beginning of each year, 600 from each tribe. The jurors had to make the following oath:

I will cast my vote in accordance with the laws, and with the decrees of the assembly and of the council and if there is no law in accordance to what I consider most just, without sympathy or enmity. I will cast my vote only on the matters brought up in the charge and will listen impartially to the accusers and defendants. [124]

Every year, the Athenian people also appointed about 1100 magistrates, who dealt with military, religious, financial, administrative, and judiciary duties. They were generally appointed by lot, but there were some important exceptions. The most important of these was the college of ten strategoi (“generals”), who were appointed by popular vote and could get reelected an unlimited number of times. They were the commanders-in-chief of the Athenian army. The army itself, however, was divided into ten tribal regiments.

With this system, Cleisthenes had spread the distribution of power to a degree that would even be unthinkable in our modern age (although still excluding women and slaves from politics, a topic we will discuss in a later chapter).

The Athenian Empire

When a new vein of silver was discovered in 493 BC, the Athenian politician and general Themistocles (524–459 BC) persuaded the Athenians to build a new fleet. As a result, Athens soon became the foremost naval power in Greece. The Greeks even became powerful enough to face the Persians. In 490 BC, the Athenian army clashed with the Persians at the Battle of Marathon, just 40 kilometers from Athens. In one of the most glorious days of Greek history, they defeated the vastly larger Persian army. In 480 BC, just 16 kilometers from Attica, the Greek fleet defeated the Persians once more at the Battle of Salamis. The commander-in-chief during this battle was Themistocles himself.

In 478 BC, various Greek cities joined a naval alliance led by the Athenians, called the Delian League. With the growing influence of Athens, however, the league progressively became effectively the Athenian Empire. They began to treat their allies more and more despotically, especially when some allied cities were unable to pay tribute. Members of the league also had to adopt Athenian currency, weights, and measures. Envoys visited allied towns to make sure that the new norms were enforced, and those who broke the rules had to stand trial in Athens.

During this golden age of Athens, its democracy also made some of its most famous blunders. General Miltiades (c. 550–489 BC), one of the heroes of the Battle of Marathon, just a few months after the glorious victory, failed to seize the Persian outpost of Paros and was badly wounded. A trial ensued at which he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. His sentence was later commuted to a fine, which he could not pay. He ended up in prison, where he died an inglorious death from his wounds.

Ephialtes and Pericles

A man named Ephialtes (d. 461 BC) brought Athenian democracy to its final stage. In the years after the Persian Wars, the Areopagus (the council of ex-archons) became the de facto ruler of Athens. In 462 BC, Ephialtes put a stop to this when he brought before the assembly a proposal to transfer the constitutional power of the Areopagus to the assembly. From then on, the Areopagus continued to operate exclusively as a tribunal for the trials of intentional homicide. In The Constitution of the Athenians, we read:

The power of the masses had constantly increased: the people have become the master of everything, all the decisions are taken by the assembly and the tribunals, where the people are sovereign; even the cases debated before the council have been transferred to the popular assembly. The Athenians seem to have acted wisely in this, because the few are more likely to be corrupted by riches and power than the many. [124]

Just one year later, Ephialtes was assassinated, and the political leadership of Athens passed to his deputy, Pericles (c. 495–429 BC). As the Athenian army grew in importance, the strategoi (generals) became the most powerful positions in Athens. Owing to his extraordinary charisma, Pericles was elected strategoi a record of 22 times between 448 and 429 BC. The general and historian Thucydides (c. 460–400 BC) famously said that his charisma made Pericles so influential that the city became a democracy in name only:

Pericles, owing to his rank, ability, and undisputed integrity, exercised a form of individual control over the multitude, while formally respecting their liberty; to put it in one word, he led them, instead of being led by them. Pericles never sought power by dishonest means, or resorted to flattery, and enjoyed so high a reputation that he could freely contradict them and cause their anger. Whenever he saw them arrogant and confident in spite of circumstances, with his words he would astound them to fear. On the other hand, if they were seized by panic, he was able to restore at once their confidence. In short, the government of Athens, a democracy by name, under Pericles’s guidance became a rule of the foremost citizen. [124]

Pericles promoted a number of measures to encourage popular participation in the government of the city. Most notably, he established a salary for a number of public duties, such as service in the jury-courts, which allowed the poor to leave their jobs if they wanted to let their voices be heard.

In 429 BC, Pericles gave his famous funeral speech in honor of the Athenian soldiers fallen in the first year of the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. In his speech, he praised the city’s democratic institutions, which he considered a model for other Greek states to follow. We read:

We follow a constitution which does not imitate the laws of our neighbors, but we are rather a model for others to follow. Its name is democracy, because the power lies in the hands of the many, not the few. Our laws afford equal justice to all in the settlement of their private disputes, but when it comes to reputation, we assign public offices on the basis of personal merit, and no citizen is preferred to another because he belongs to a higher social class, nor is lack of means a barrier from attaining renown and public honors for anyone who can be of service to the city. […] In a word, I say that our city is a school for Greece, and that each of us has the power of adapting himself in the most various cases of life with the greatest ease and versatility. And this is not just empty boasting. This is nothing but the truth, as the power of our city is there to demonstrate. [124]

He described Athens as a community of responsible and capable citizens who were willing to take part in the politics of the city:

In the same man one might find an equal interest in public as well as private matters, and even those citizens who are mostly concerned with their private business, do not lack knowledge of public affairs. For we are the only ones who consider the man who does not take part in public life not as someone who looks after his business, but as good for nothing. We are able to take political decisions by ourselves or submit them to thorough discussion, for we believe that debate is not an obstacle to action. Rather, we think that careful discussion is an essential preliminary to action. [124]

The democratic constitution also allowed a good balance between the public duties of the citizens and their private lives. Unlike the Spartans, the Athenians did not regard military training or service to the state as the only purpose of their lives. Nevertheless, they were valiant soldiers on the battlefield. We read:

We are also different from our enemies in our approach to military matters. We keep our city open to the world, and never expel foreigners to prevent them from learning or seeing anything which, when revealed, an enemy might find useful to know. For we place our trust less in deceit and machinations than the bravery of our men on the battlefield. If we turn to education, while our enemies since the earliest age have to undergo the most toilsome training in their pursuit of manly courage, we live a life free from constraints and yet are just as prepared to encounter the dangers of war. [124]

Pericles died of a plague that broke out in Athens in 429 BC. According to Thucydides, his death was a disaster for Athens since his successors were greatly inferior to him.

A few years later, in 423 BC, the famous playwright Euripides (c. 480–406 BC), in his play The Suppliants, also spoke favorably about democracy. In this play, he described Theseus, the fictional founder of Athens, as the founder of democracy:

For I have made the people (demos) sovereign and set the city free by giving all the citizens equal right to vote. [124]

When a Theban messenger arrived in Athens, he asked for the “tyrant” of the city. The Athenians explained they had no such thing:

Foreigner, you have given a false beginning to your speech by seeking a tyrant here. For this city is not ruled by one man, but is free. The people are sovereign here, ruling in succession year by year. No preference is granted to wealth, but the poor has an equal share with the rich. [124]

Fig. 317 – Roman copy of a bust of Pericles (original from c. 440 BC) (Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5; British Museum)

The Peloponnesian War

As the Athenian empire grew stronger, the Spartans felt increasingly threatened, leading in 431 BC to the Peloponnesian War. When, in 406 BC, the Athenian fleet engaged in battle with the Spartans, a violent storm broke out that took the lives of many Athenian soldiers. When the Athenian officials failed to recover the bodies, the people of Athens became enraged. The generals in charge of the operations were removed from office, and when they returned to Athens, they had to stand trial before the assembly and were sentenced to death. This was another tragic mistake of democratic Athens. Depriving Athens of its most experienced generals contributed greatly to its defeat and surrender in 404 BC at the hands of the Spartans.

But the Spartan empire didn’t last either. It came to an end during the Corinthian War when the Persians allied with the Athenians and attacked the Spartans. The war ended in 387 BC with a peace treaty, which gave Persia control over Ionia. For a short time, democracy was restored, but not for long since, in 338 BC, the Macedonians took over Greece (as we will discuss in a later chapter).

Aristotle on democracy

Aristotle, in his work called Politics, studied various types of government and tried to work out which system was the most beneficial. He believed a monarchy could work, but only when the monarch was virtuous and worked in the common interest of the people. But having a monarch was also risky since he could easily turn into a tyrant, ruling according to his own interest. An aristocracy, where a small group of elites was in charge, could also work if these elites were virtuous and qualified. However, this type of rule could easily turn into an oligarchy, motivated by the acquisition of wealth. Finally, he mentioned democracy. Democracy, he claimed, is founded on the principle of liberty. We read:

In an aristocracy, power belongs to a group of individuals of superior worth, as defined by birth, personal merit, and not by any “arbitrary standard.” Democracy, on the other hand, is a form of government whose fundamental principle is liberty. In a democracy, political power is not an exclusive and permanent possession of a small group of citizens or just one of them.

One of the elements of liberty is to rule and be ruled in turn, for the democratic notion of justice is based on numerical equality, not on merit. [From this] it necessarily follows that, in a democracy, the people are sovereign and the decisions of the majority are final and constitute justice, because, as they say, every citizen must have an equal share in the government.

Consequently, in a democracy, the poor are more powerful than the wealthy—because there are more of them—and any decision approved by the majority is sovereign. This is one of the elements of liberty, which democrats set down as an essential principle of this kind of constitution. Another one is that everyone should live as they please. This, as they say, is the objective of democracy, because the man who cannot live as he pleases is a slave. This is the second principle of democracy. Based on this principle comes the claim that men should be ruled by no one if possible, and, if that is not possible, they should rule and be ruled in turn. [124]

However, this system could easily turn into mob rule, where the majority blindly suppresses the wise few. We read:

While oligarchy is defined by birth, wealth, and education, democracy seems to be defined by the opposite of all these: low birth, poverty, and ignorance. [124]

Aristotle’s solution to this problem was to put the power not in the hands of either a few rich elites or the poor majority, but to instead give power to the middle class. In his view, the members of the middle class are best suited to rule because they are educated and always looking for ways to improve themselves. Unlike the rich and the poor, they have less to gain from politics and are largely satisfied with what they have, which makes them the most likely to govern with the common interest at heart. They can also act as a mediator between the poor and the rich, creating a stable middle ground. With their education and larger number, they might even collectively make better decisions than a virtuous few. Finally, Aristotle also advised the government to prevent extreme poverty, as this “causes democracy to be corrupt.” This should be done not by giving them free grain (“because this way of helping the poor is the legendary jar with a hole in it”), but by helping them get a job and stand on their own feet.

Critics of democracy

Critics of democracy often preferred the oligarchic constitution of Sparta, which they considered to be the world’s most perfect system. To them, democracy was just an endless stream of bureaucracy, disorder, and hasty decisions based on the whim of the population. The rhetorician Isocrates (436–338 BC) wrote:

We claim [...] that our city was founded before all the others, but although we should be an example of good and orderly government to everyone, we run our city in a worse and more disorderly manner than those who are just founding theirs. [124]

And:

We pass an enormous quantity of laws, but we care so little about them.

About the inconsistency of popular thought, he wrote:

We are the best masters of public speaking and politics, but we are so inconsiderate that we do not hold the same opinion on the same matters on the same day.

An especially fierce anonymous critic

described democracy as a wicked yet efficient system, deliberately devised to

give the highest degree of power and license to the worst citizens, while the

political and financial burden of the city was left on the shoulders of the

wealthy and the respectable.